By Melanie Williams

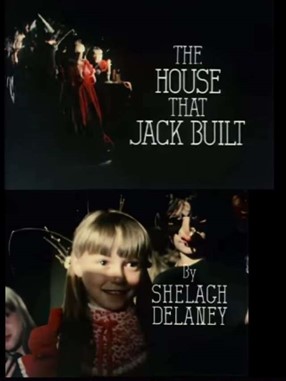

The writer Shelagh Delaney remains best known for her first play, A Taste of Honey, produced by Theatre Workshop in 1958 and revived many times since, also adapted into a multi-award-winning film by Woodfall in 1961. This dazzling debut has tended to overshadow the array of other work she did throughout her career. It seemed that Delaney’s meteoric trajectory, writing an international hit play while still a teenager, demanded a matching downward curve on the parabola. Nonetheless, despite never recapturing the level of cultural impact she had with A Taste of Honey, it would be a mistake to write her off as a one-hit-wonder. She did excellent work across all the decades in which she was active as a writer, spanning a wide range of media: theatre, film, literature, radio and television. However, the longer-term inaccessibility of some of this work, especially her writing for television (despite its large audience reach at the time), has inevitably had an effect on her critical reputation, rendering less visible key aspects of her mature career. When I was researching Shelagh Delaney, her TV dramas proved the hardest part of her oeuvre to access, and I am very grateful to both Christine Geraghty and Billy Smart for alerting me to and then facilitating access to the example of Delaney’s television work that I’m going to be writing about here: her six-part BBC drama The House That Jack Built (1977).

Delaney’s entanglement with television drama had actually begun very early on in her writing career. Both the BBC and Granada’s drama departments made overtures to the enfant terrible in the wake of her great success with A Taste of Honey. That play had also acted as an important inspiration for Tony Warren in creating his own long-running (to put it mildly) slice of Salford life, Coronation Street (Granada/ITV, 1960- ), and he had, in fact, invited Delaney to write for the serial; an offer she turned down because she saw its depiction of a Northern community as ‘cap and muffler’ territory, suggesting Lowry-esque nostalgia rather than the edgier work she wanted to pursue.[i] She did accept a later offer to write for the BBC’s innovative police series Z Cars (BBC, 1962-78), while the screen adaptation of her own short story, The White Bus, which would end up being a featurette for Woodfall films directed by Lindsay Anderson, had begun as a putative Wednesday Play project, hamstrung by the unwillingness at that point to leave the studio and film on location, as the piece demanded. Delaney would later contribute single plays to the drama anthologies Thirty-Minute Theatre (BBC) in 1970 and Seven Ages of Woman (LWT) in 1974 – although ironically, the most substantive legacy of that latter series was not any one of its individual plays but its specially composed theme tune: ‘She’ sung by Charles Aznavour. Her most substantial television work came with The House That Jack Built. Given a free choice of a project by the commissioning BBC, Delaney chose to return to some of the material she’d first addressed in her second play, the far less celebrated The Lion in Love (1960), relating to the frustrations and compromises of marriage and their culmination in marital breakdown.[ii]

In contrast with Delaney’s previous forays in television, The House That Jack Built offered an extended canvas on which she could present her own ‘scenes from a marriage’, to borrow the phrase from Ingmar Bergman’s unsparing drama of relationship breakdown, which had been on both small and big screens a few years before, and indeed was being shown on BBC2 around the same time as Delaney’s series was transmitted. Bergman’s core couple were middle-class intellectual professionals inhabiting the desirably airy spaces associated with the Scandinavian bourgeoisie. In contrast, Delaney’s married couple, Jack (Duggie Brown) and Lu (Sharon Duce), are located in a different class and place altogether.

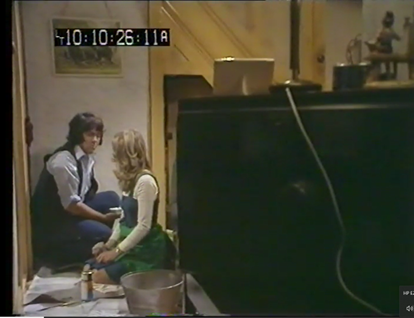

Jack (Duggie Brown) and Lu (Sharon Duce) try to sort out an infestation of mice in episode two, ‘Eight Years Ago’. The back of the television dominates the mise-en-scène, an interestingly meta-textual compositional choice.

Delaney demonstrates deep engagement with the relationships between people and the places they live in at the granular levels of street, house, and room. As the construction-themed title of the series suggests, this drama is about building; the building of a house is an enterprise not only analogous to but also inextricable from the building of a marriage, although Jack is not the only builder involved in this, with Lu an equal co-creator. As Delaney herself put it: ‘They are building something physical and emotional, and sometimes something collapses, and they build it up again.’[iii] They debate their plans, worry over budgets, apportion work, experience stoppages and unrest, accomplish some things, and fail to achieve others. But although this portrait of a marriage emphasises its practical aspects, Delaney took care to invoke its spiritual dimensions too: ‘They enter into a sacrament. That’s the important thing. They’re married in a Catholic church […] It’s a divine state, isn’t it?’.[iv] Although Delaney never married herself (perhaps because she never married), she shows great insight into the ambivalences and complexities of the married state, its quotidian incidents and conversations, but also its greater meaning and significance.

The series chronology provides the drama with an interesting structure, as each episode presents a different moment during their decade-long marriage, from their far-from-romantic wedding night, complete with a vomiting bride to a moment of rapprochement between them during their trial separation when it’s the husband’s turn to be violently ill. The first episode is set ten years ago, the next one eight years ago, and so on until reaching the present day. In addition, the productive constraints of studio production are used to great effect across the episodes, matching the constraint of the two-hander dramatic form (handled with great skill by both Brown, best known as a comedian at the time, and Duce). In each episode, we are confined to the couple’s ground floor living area, initially on a shabby terrace in what Jack regards as a rough area, and in later episodes, a bay-windowed house on a semi-rural estate. Although the ebb and flow of the marriage is undoubtedly affected by their current living situation, it is not simplistically reducible to it. There are pros and cons to both locations. For instance, Lu gains a garden in the new house, which she loves cultivating, but she sees less of Jack, partly because they have a higher mortgage to pay during harder economic circumstances. But this has as much to do with his increasing disengagement from home and family and his growing interests elsewhere.

The end of an era: Lu and Jack’s vacated house, soon to be demolished, at the end of episode three, ‘Six Years Ago’.

This is a story of upward social mobility in some respects, but the impetus for their move came more from the compulsory purchase order they received for the demolition of their old street to make way for a high-rise than any property-ladder-climbing ambition. Every home they live in exacts its penalty. It is a subtle running joke that whichever home they’re in, Jack ends up scrabbling about in the dark under the floor, whether gathering fuel from the coal hole in their two-up, two-down or trying (and failing) to fix the central heating in their new home. Against the obvious sense of difference and development in Jack and Lu’s habitat (and in their relationship), which the series tracks, there is a powerful counter-melody of continuity and repetition. It is poignant to see the same furniture appearing across every episode, albeit in slightly different arrangements, with the living room mirror proving an especially expressive piece of set dressing, used to showcase the couple’s interactions in visually telling ways (kudos to designer Dick Coles and director Peter Hammond) as well as suggesting the cumulative meaning accrued by familiar household objects over time.

The same over-mantle mirror across episodes two (adorned by a never-explained Frankenstein mask), four and five.

Seeing Jack reflected in the mirror also harks back to the little piece of folklore enacted in the title sequence. A group of young girls are trying the Halloween ritual of brushing their hair three times in the mirror by candlelight while holding up an apple, hoping this will reveal the face of the man they will marry reflected behind them. Young Lu sees young Jack appear behind her, and she looks distinctly underwhelmed by the prospect. But he’ll keep on appearing in the mirror through these vignettes of their marriage, underlining their possible predestination as a couple.

From the opening credits to each episode, Lu sees Jack in the mirror in a childhood ritual.

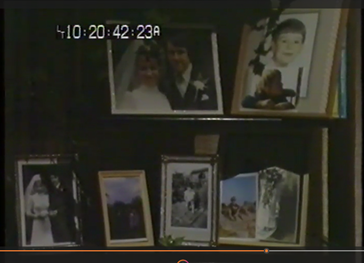

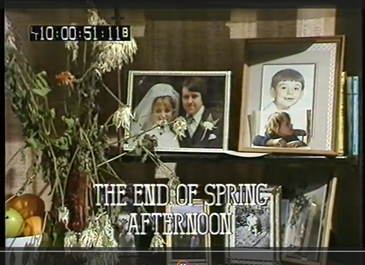

Lu worries that she is becoming part of the furniture, ‘a stopgap while you waited for something better to turn up’, and resents her economic dependence on Jack. We see her gain greater confidence when she goes back out to work. Gender roles are held up to the light and scrutinised, as they are in all of Delaney’s work. Delaney described Jack and Lu as ‘cowboy and a Madonna’, perhaps gesturing towards the images others project onto them as much as their own idealised self-images.[v] Meanwhile, it is significant that in its investigation of marriage, The House That Jack Built studiously avoids romanticising parenthood, and indeed, the couple’s two young children are never actually seen in the drama, except in photographs and indirectly through the presence of household possessions like the pram. They are part of the story, but Delaney’s focus throughout stays unswervingly on the shifting psychodynamics of coupledom and cohabitation, where suspicion, resentment and drudgery are counterbalanced with connection, pleasure and laughter. The love language of Lu and Jack is acidic badinage and backchat, which, as Lu reflects, bespeaks their absolute intimacy: it takes ages before you can be that rude to someone. We are not that far away here from the kind of crackling banter Delaney wrote for Jo, Helen and Geoff in A Taste of Honey, but arguably now with the deeper insight into human interaction afforded by age and experience.

The same family photographs on the same shelf, but the dead flowers in the final episode imply the changed context.

It begins to dawn on the couple quite early on that they are different personalities, with the Donne-quoting dreamer Jack being called out by Lu on his unwillingness to realise any of his dreams even when they are potentially achievable: ‘For all your extravagant talk you’re just as stuck in the mud as everyone else. I admit my visions are a bit thin on the ground, but when something does take my fancy, I like to see it develop.’ They are locked in loving combat throughout; there is never a moment’s ease. By the end, they are living apart, but Lu’s options for living independently are severely limited, and she still feels a residual affection for her husband. The bond is frayed but not quite broken, and anyway, as Jack tells her in the closing words of the drama: ‘look at it this way, Lu. If I don’t have you, some other lout will’. What exactly comes next for the couple is left undecided. But it was certainly a situation of increasing familiarity for its audience as the divorce rate in England and Wales increased during the 1970s, something the drama alludes to when the couple talk about half the people they grew up with being in the throes of separation. Interestingly, Delaney said around this time that she created ‘fairy stories’ in her work: ‘Everything I write could begin with “Once upon a time…”’.[vi] There are certainly fairytale elements to the story – the derelict castle Jack wants to buy, the movie monsters he imitates, Lu’s golden party shoes – but whether the couple get to live happily ever after is a moot point.

Nancy Banks-Smith’s review of the opening episode of The House That Jack Built ended: ‘Watch it. I commend and recommend it to you.’[vii] I would like to repeat this but with the regretful caveat that it is unlikely that you will be able to watch it without special archival affordances. This is a pity as there is much in Delaney’s writing for this series to match and even best her much more celebrated work, as exemplified by A Taste of Honey. But I commend and recommend it in the hope that it might one day be as readily accessible as some of Delaney’s other work and, therefore, underline the breadth of her talents as a key post-war British dramatist.

[i] These entanglements with television are covered in Selina Todd’s fascinating and thorough biography, Tastes of Honey: The Making of Shelagh Delaney and a Cultural Revolution (London: Chatto & Windus, 2019).

[ii] She’d also come back to this territory in her screenplay for Charlie Bubbles (1968), featuring a couple who are already divorced, with Billie Whitelaw playing the thoroughly cynical Lottie Bubbles who is, frankly, sick of her ex-husband Charlie’s shit. Delaney would go on to explore an even darker relationship dynamic in her screenplay for the Ruth Ellis biopic Dance with a Stranger (1985).

[iii] John Cunningham, ‘The Salford Madonna’, The Guardian, 4 August 1976, p. 9.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Nancy Banks-Smith, ‘House that Jack built’, The Guardian, 16 June 1977, p. 10.

Melanie Williams is Professor of Film and Television Studies at the University of East Anglia. Her most recent book was a BFI Film Classic, A Taste of Honey (Bloomsbury, 2023). Previous books include David Lean (MUP, 2014) and Transformation and Tradition in 1960s British Cinema (EUP, 2019). She is currently working on a monograph on the British filmmaker Muriel Box.