By Dr. Bruna Foletto Lucas

Six years after its release, The Devil’s Doorway remains a compelling and relevant film, particularly given its continued resonance with contemporary social issues. Directed by Aislinn Clarke, the first Irishwoman to write and direct a feature-length horror film, The Devil’s Doorway offers a unique and haunting exploration of Ireland’s Magdalene laundries. Clarke’s idea for the film originated a decade before its creation, stemming from her research for a documentary on the subject. The topic holds personal significance for Clarke, who noted that “Lots of people in Ireland, North and South, have stories – personal stories, family stories – about those places.”[i]

Magdalene laundries were Roman Catholic institutions purportedly designed to rehabilitate “fallen women”—a term used to stigmatise sex workers and women who had children outside of marriage. Over time, these laundries evolved into mechanisms for maintaining patriarchal values and exploiting a free female labour force. Frances Finnegan, author of Do Penance or Perish: Magdalen Asylums in Ireland (2004)[ii], notes that the original moral and social motives behind these institutions gradually shifted towards economic exploitation and systemic oppression.

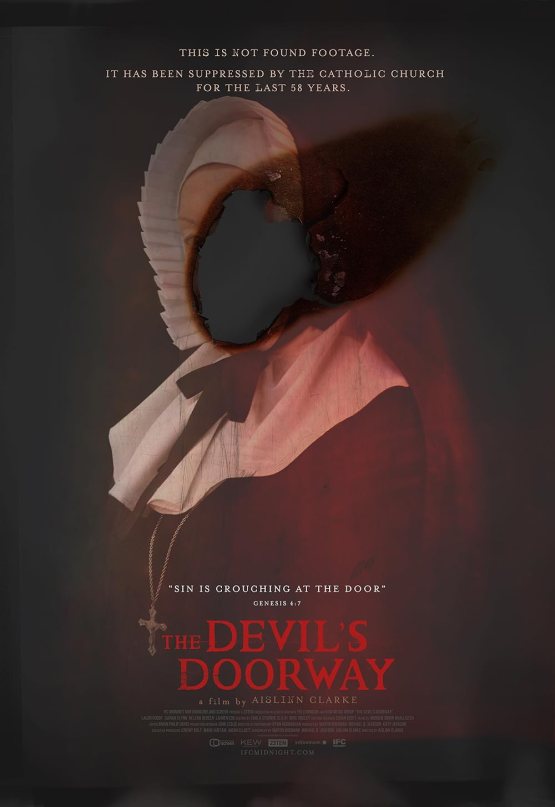

This is the starting point of The Devil’s Doorway – disguised as a horror film, Clarke’s feature investigates the role of religion as a tool for enforcing conservative, oppressive values on women. Similar to other horror films released in the same year, such as Tau (D’Alessandro, 2018), Cam (Goldhaber, 2018), Unsane (Soderbergh, 2018) and Wildling (Böhm, 2018), Clarke’s work underscores the importance of female perspectives in horror, contributing to the genre’s evolution towards more inclusive and socially aware narratives. As the first woman to write and direct an Irish horror feature, Clarke has positioned Ireland within the western shift towards female-oriented horror. The themes of patriarchal oppression and female victimhood in her film continue to resonate in contemporary horror, particularly in works directed by women. Films like Run Sweetheart Run (Feste, 2020), Medusa (da Silveira, 2020), Watcher (Okuno, 2022), Fresh (Cave, 2022), The Invitation (Thompson, 2022), Huesera: The Bone Woman (Cervera, 2022), and the horror-adjacent Don’t Worry Darling (Wilde, 2023) and Run Rabbit Run (Reid, 2023) share a thematic kinship with Clarke’s film, highlighting the ongoing relevance of these issues.

The film’s narrative follows two priests, Father Thomas (Lalor Roddy) and Father John (Ciaran Flynn), who are sent by the Vatican to investigate reports of miraculous phenomena at a Magdalene laundry, where a statue of the Virgin Mary is said to be crying blood. The story is presented in a found footage style, with Father John operating the camera, lending an immersive, documentary feel to the film.

While the film does include some conventional jump scares, it excels in building atmosphere and tension. Clarke’s skilful manipulation of suspense keeps viewers on edge, with the threat of supernatural occurrences often proving more unsettling than the actual manifestations. The film’s true horror, however, lies in its depiction of the brutal treatment of women within the laundry, a reality that deeply disturbs Father Thomas. The women’s suffering is palpable, raising questions about whether they are the source of the danger or its victims.

Father Thomas and Father John are contrasting characters, with the younger Father John more open to believing in the paranormal, while the older, disillusioned Father Thomas has lost faith in both divine and diabolical explanations for the world’s ills. He cynically observes that human actions are often the root cause of both good and evil.

As their investigation deepens, the priests uncover evidence of Satanic practices by the nuns, leading to more traditional horror elements, including exorcism scenes. These moments, though somewhat conventional, are overshadowed by the film’s atmospheric build-up and its unflinching portrayal of institutional abuse, continuously maintaining its theme of female oppression and punishment. The Mother Superior hints at the rapes suffered by the women at the hands of priests and categorizes all the women as “not all good girls in this home.” The women are revealed to be victims of cruel punishments imposed to ensure discipline and are exploited for labour, responsible for both maintaining the asylum and running the local laundry business.

Clarke’s feature debut excels in pacing and atmosphere, showcasing her deep understanding of the horror genre –as a filmmaker, a fan and a scholar. Beyond its effective scares, The Devil’s Doorway bravely tackles the dark history of the Magdalene laundries and the systemic abuse perpetrated by the Catholic Church. Filmed entirely in Northern Ireland, the film’s exploration of religious and patriarchal oppression is both audacious and necessary, cementing Clarke’s place as a significant voice in contemporary horror cinema.

[i] McGrew, Shannon (2018) Interview: Director Aislinn Clarke for THE DEVIL’S DOORWAY. Available: https://www.nightmarishconjurings.com/2018/07/10/interview-director-aislinn-clarke-for-the-devils-doorway/(Accessed: 21/05/2024)

[ii] Finnegan, Frances (2004) Do Penance or Perish: Magdalen Asylums in Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

This article is the expanded version of Foletto Lucas’s previous work available here.

Dr. Bruna Foletto Lucas (she/her/hers) is an early career researcher focusing on the intersections of horror and gender. Her PhD thesis (‘Reclaiming Horror: Understanding the Paradigm Shift of Female Representation in Horror Films’) examines the nuanced transformations within the genre. Bruna’s academic pursuits extend beyond her PhD, with ongoing work on various publications and presence at international horror conferences and events, including the Miskatonic Institute of Horror Studies London and the Final Girls Berlin Film Festival.